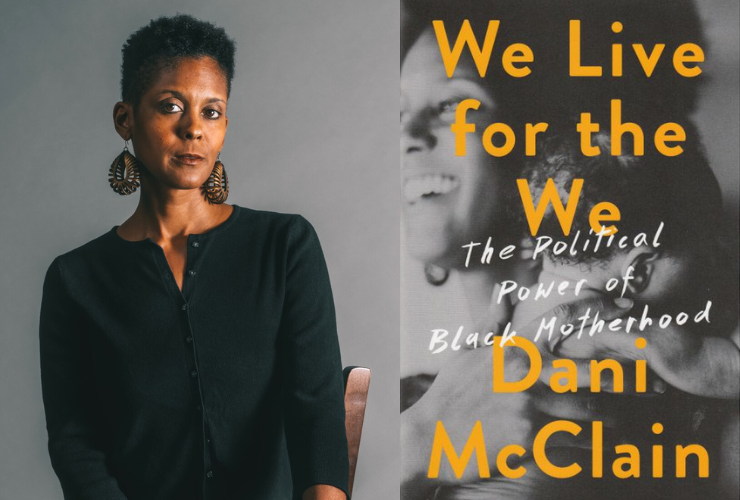

On September 22nd, 3:00 to 4:00pm EST, The National Library of Medicine is hosting a special book club event in partnership with the Black Women’s Health Imperative to support awareness of the All of Us Clinical Research Program. The book we are reading is We Live for the We, the Political Power of Black Motherhood by Dani McClain. During the book club, Dani will be in conversation with our contributor, author Andrea King Collier.

Andrea had the chance to talk with Dani about her book and how it informs Black women’s health.

What drove you to dig into this important subject?

When I was pregnant with my first child, I had a lot of questions about how to best raise a black child in the United States today. I was in my third trimester during the summer of 2016. That was the summer that Philando Castile was killed in the Twin Cities and Alton Sterling was killed in Baton Rouge, both by police. The “Blue Lives Matter” and “BLM organizers are domestic terrorists” messaging was gaining traction in mainstream media, and far-right rhetoric was being lifted up and legitimized by the Trump campaign. At the same time, the Mothers of the Movement — the mothers of people including Sandra Bland, Jordan Davis, Eric Garner and Trayvon Martin — were on the DNC stage, talking about having lost their children to police and vigilante violence. I was also reporting a story that summer about the black maternal health crisis. I realized that all of these questions and conversations deserved to be taken up in a book-length project.

The numbers aren’t new. Why do you think this is finally getting the attention and action from the medical and public health communities ?

Media attention has a lot to do with it. That black maternal health story that I was working on in the summer of 2016 ran as a cover story in The Nation in February 2017. It combined research and reporting with my own experiences as a black woman seeking prenatal care, interacting with health care systems and delivering in a hospital. Soon after, there were important and high-profile series and articles in The New York Times Magazine, on NPR (through their partnership with ProPublica) and elsewhere. These stories had been covered before, but suddenly they were appearing in prestige media outlets. The issue had been framed previously as a US maternal health crisis, and more recently we’ve gotten clear that this is a crisis that primarily affects black and indigenous families. We’ve heard Beyoncé and Serena Williams tell their birth stories, and hearing harrowing reports from black celebrities drives home that the issue is race, not class. Racism is finally being named as a reason that black women aren’t being listened to and aren’t receiving the care they need.

Some of the disparities come from disparities in chronic health conditions and stress. Who is doing a good job of looking at Black women holistically according to your research and interviews?

There are so many people working on these issues that I hesitate to name them. I can think of stories that I’ve written for SELF, for ZORA, for The Nation that lift up the research and experience of scholars and clinicians who are trying to improve outcomes for pregnant and birthing black women. I’ve been particularly interested in speaking with black birth workers — midwives, obstetricians and doulas — because their perspectives have traditionally been underrepresented in media coverage of maternal health. Early in my reporting I was encouraged to consider the following: If racism or implicit bias plays a role in black birthing people not receiving the care they need, what happens if you look at what happens with black providers? If cultural congruence — a phrase that I learned from a DC-based nurse midwife named Anayah Sangodele-Ayoka — is present, how does the quality of care change? I’ve tried to explore that question through my reporting.

What can Black women as a “community” do to support each other?

Many people I’ve interviewed talk about the importance of finding a circle of support during pregnancy, a group of other pregnant people and families with whom you can share your questions and concerns and get answers from an experienced birth worker. In WE LIVE FOR THE WE, I write about joining a birth education group through a local hospital. My daughter’s father and I were one of two black couples in a group of about a dozen couples. There were things that were relevant to my experience (such as carrying a pregnancy alongside large fibroids, and generally being concerned about preterm birth and other conditions that disproportionately strike black women) that just didn’t come up in the group, and when I brought them up they weren’t adequately addressed. So, these circles of support need to be culturally appropriate. These circles of support continue to be necessary postpartum as well. People who have just given birth need a team to help with food, to ensure that everyone is resting as much as possible, to make sure that medical attention is sought when it needs to be. This reliance on a community is essential in pregnancy and birth but also in the early stages of the newborn’s life and, of course, beyond.

What was the most surprising thing to you?

Florida-based midwife Jamarah Amani explained to me how public health officials in the early 20th century began to frame the use of midwives and home birth as backward, dirty, dangerous. I didn’t know this history, but listening to people like Amani and watching the 1953 documentary “All My Babies” opened my eyes to the important role granny midwives played and how they were disappeared and driven underground by progressive-era public health reforms, essentially to make way for the male-dominated medical approach to birth. Amani also helped me see how the racial makeup of birth workers has changed. I quote her in my book as saying, “There were close to 4,000 midwives in Florida at the turn of the 20th century, and now we have under 200. The overwhelming majority of those 3,000-plus were black, and now the overwhelming majority of those 200 are white.” I’m very curious about how outcomes change if we examine more closely who is helping us through pregnancy and birth and the values, beliefs and skills they bring.

What gives you hope in terms of impacting outcomes?

The conversations in progress today give me hope. The policy changes being introduced as bills at the federal and state level give me hope. I’m interested in these counties and municipalities declaring racism as a public health crisis. I’m curious what the impact of that will be. Traveling around the country to promote the book I was able to speak to groups that are creating those circles of support, groups like Bloom Collective in Baltimore, the Mothers to Mothers Postpartum Justice Project in the San Francisco Bay Area, Queens Village in Cincinnati, where I live, just to name a few. Community-based efforts like these give me hope.

You spent some time talking to the team at Henry Ford Health System in Detroit about their WINN program. Why did you go to them? And what are they doing that can be modeled in other places?

I’d heard that Henry Ford was doing interesting work with group prenatal care for women at high risk for preterm labor. They were also connecting women with community health workers who could help them with things like access to healthy food, stable housing, reliable transportation. This appeared to be a hospital system trying to provide women with that circle of support that I’d heard was crucial, and I learned that their outcomes were impressive. Of the 25 babies born to participants in the 2016 pilot, none were sent to the neonatal intensive care unit. Only one was born under a healthy weight. None of their mothers were sent to the ICU, and all of them started breastfeeding and were connected to lactation support. I’m curious how and where similar efforts are cropping up around the country.

About Dani McClain

Her writing has appeared in Slate, Colorlines, EBONY.com, The Rumpus, Guernica, The Atlantic and The New York Times. Dani McClain is a contributing writer with The Nation and a fellow with Type Media Center.

McClain reports on race, parenting and reproductive health. In 2018, she received a James Aronson Award for Social Justice Journalism. The award recognizes writing that addresses widespread injustices, their human consequences, underlying causes, and possible reforms.

Her work has been recognized by the National Lesbian and Gay Journalists Association, the National Association of Black Journalists, and Planned Parenthood Federation of America.

She has also worked as a strategist with organizations including Color of Change and Drug Policy Alliance.

Her book, We Live for the We: The Political Power of Black Motherhood, was published last year by Bold Type Books and is a finalist for the 2020 Hurston/Wright Legacy Award in Nonfiction.