It’s been a few days since your annual gynecologic exam. The phone rings. It’s your physician, letting you know that you have an HPV infection.

Huh?

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is the number-one sexually transmitted infection (STI) in the U.S. STIs can carry a stigma, but HPV is not something to be ashamed of. HPV is so common that most people who are sexually active will get it at some point in their lives.

There’s a whole lot of information about HPV floating around out there, so it’s important to get the correct answers to your questions.

What exactly is HPV?

Let’s start with the basics.

HPV isn’t one virus. It’s actually a group of more than 200 related viruses. About 40 of them can affect your genital area. But “affect” is different than “effect.” Most people with HPV don’t ever develop symptoms or health problems.

There are two categories of HPV viruses: low-risk and high-risk.

Low-risk HPV viruses can cause genital warts, but they rarely cause cancer.

High-risk viruses can lead to several types of cancer, including those in the cervix, vagina, vulva, penis, anus, and back of the throat.

But don’t freak out just yet if you have a high-risk one. Even high-risk viruses tend to clear up on their own, without causing cancer.

How will I know if it’s cancerous?

If you’ve been diagnosed with a high-risk HPV, your physician will probably want to perform a colposcopy. During the colposcopy, she will use a colposcope (similar to a microscope) to take a closer look at your vagina and cervix.

At the same time, she may perform a biopsy where she removes the infected cells to check for signs of cancer.

We’ll be straight with you. These tests can be a bit uncomfortable. But they’re very quick, and there’s usually no lingering pain afterwards.

And the tests can help you catch signs of cancer early on, when it’s easy to treat. So, take a deep breath, pop some ibuprofen, and push through it.

How did I get it?

More often than not, it’s simple: You had sex. Any type of sex can lead to infection, whether that’s vaginal, oral, or anal sex.

It’s also possible to get it from skin-to-skin contact with the part of your partner’s body that’s infected, or from shared sex toys.

You won’t get it from holding hands, swimming in pools or hot tubs, or sharing food. You also won’t get it from objects like toilet seats or utensils.

You’re more at risk for getting HPV if you have unprotected sex, or sex with multiple partners. But even if you’ve only been with one person, you can still get it if your partner has been with someone else.

Can I get rid of it?

Sort of. There isn’t a cure for HPV, but your body will probably get rid of it naturally. About 70% of new HPV infections clear up within a year, and 90% are gone within 2 years.

There are some cures for symptoms, like prescriptions to clear up genital warts, but they won’t actually remove the virus from your body. And if your infection shows precancerous cells, your physician might remove those cells to try to prevent cancer.

I got that vaccine, and I still got HPV. Explain, please.

If you got the vaccine but still got HPV, it doesn’t mean that the vaccine didn’t work.

There are three HPV vaccines approved by the Food & Drug Administration (FDA): Gardasil, Gardasil 9, and Cervarix. All of these prevent infections with the high-risk HPVs (types 16 and 18) that are responsible for about 70% of cervical cancers.

In addition to these two types, Gardasil prevents the types known for causing 90% of genital warts (types 6 and 11). Gardasil 9 protects against the same four as Gardasil, plus five other high-risk HPVs (types 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58).

That might seem like a lot of protection, but remember—there are more than 200 types of HPV. That means that while you may be protected from certain types, you’re still at risk for getting the others.

Real talk: How will this affect my sex life?

Once you’ve been diagnosed with HPV, it’s more important than ever before to use protection. While condom use can’t provide 100% protection, it can definitely decrease the risk of giving HPV to your partner. And since you can get multiple types of HPV, condoms will also protect you against getting another type.

HPV also means it’s time to take responsibility when you’re with a new partner. Even though it’s very common, and your partner may already have it, it’s important to let your partner know about your diagnosis. Give him or her the straight facts on HPV, without approaching it as a “confession,” or something to be embarrassed about.

Your honesty will build trust. And if (s)he doesn’t want to be with you because you have HPV, or if makes you feel bad about it, then (s)he’s not worth your time, anyway.

Can I still get pregnant? Will I pass HPV to my child?

If your HPV turns into cancer, certain cancer treatments can cause infertility. But for the most part, HPV shouldn’t stop you from getting pregnant. (And no, the vaccine has not been shown to affect fertility, either).

Don’t worry if your genital warts get worse. Discharge, and changes in hormones or your immune system during pregnancy, can make warts grow faster. It’s unlikely that warts will affect your baby’s health.

You also don’t need to stress about passing HPV to your child. There have been cases where moms have given the type of HPV that causes warts to their unborn baby. But these cases are extremely rare. And even if this does happen, your child will most likely be able to overcome the symptoms.

Should I get my child vaccinated?

Yes, ma’am. It doesn’t matter if you have a boy or a girl—either can benefit from the vaccine.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that all kids ages 11 to 12 get vaccinated. It’s okay if they miss that deadline—your child’s physician can work with you to get your kid vaccinated up until age 26.

I’ve been in a relationship for a year, and just found out I have HPV—and my man told me he was clean. Is he a cheater and a liar?

HPV is not a sign that your man’s got someone on the side or is keeping you in the dark. There are a few reasons you can be diagnosed with it while you’re in a monogamous, honest relationship.

One is that HPV can linger in the body for years before it’s diagnosed. You could have gotten it from a previous partner, but it’s only just started to make an appearance, or vice versa.

There is no reliable test for men. Your partner may show you a clean STI panel, but he could still have HPV and not even know it.

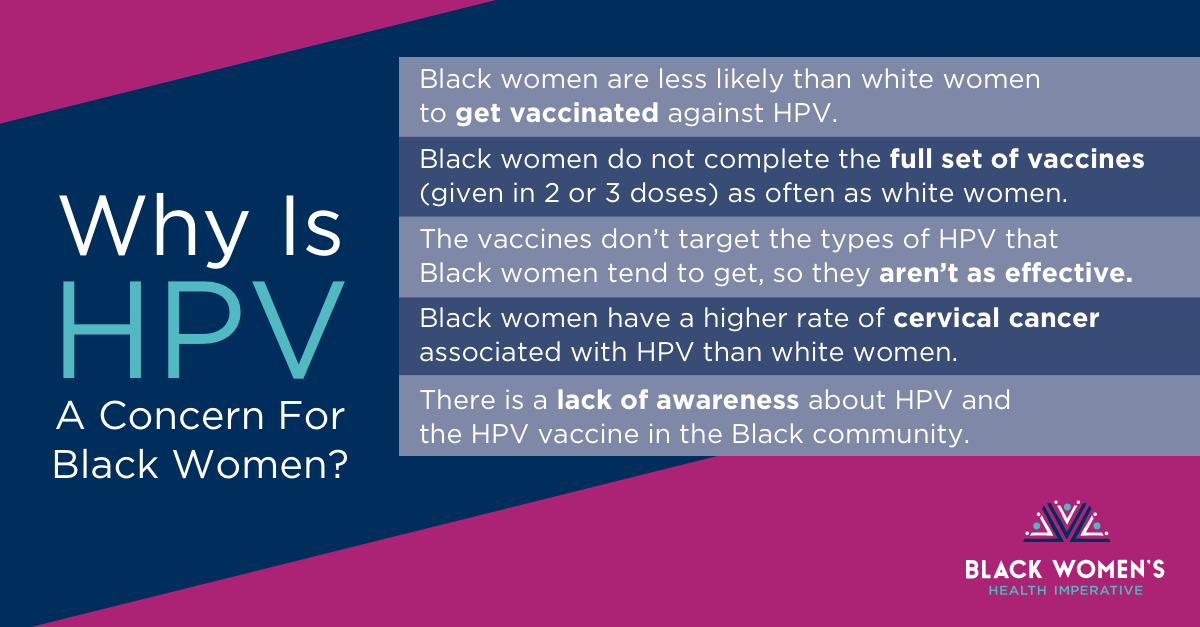

Does HPV affect Black women differently than white women?

Yup, you guessed it—there are some differences between HPV in Black women and HPV in white women.

Here’s how HPV affects Black women:

Since so many sexually active people get HPV, chances are good that you know someone else who has it, too. Make sure they know the scoop on living with HPV.